Angkong's Kitchen and Awa's Lukadan

Written by Nyel O’Yek

Papa methodically broke several barbecue sticks in his hand so that they fit the kawali's diameter steadily. He formed a crisscross and put a lapu-lapu in the middle. Underneath, he poured water.

Sunlight entered our kitchen windows in Quezon City like a spotlight illuminating the pan. I looked on, amazed at my father who went from garnishing the fish with onion springs—his hands moving in a calculated motion—to lighting a match with one smooth swish, to switching on the gas range. Who was this wizard? What was he doing?

“Cooking,” he said.

“In water?” I asked.

My father explained that this is the way one steams fish. At 6 years old in the '80s, I did not know it was possible to cook like that—with sticks crisscrossed in the pan, water gently boiling underneath.

What just happened before me did not look like that word “cooking.” I remember my 6-year-old brain struggling to match the movement with the action word, and by then I had seen enough wizards in cartoons to recognize that my father was performing some alchemy. I remember asking Papa then how he learned to cook—did his Papa also teach him?

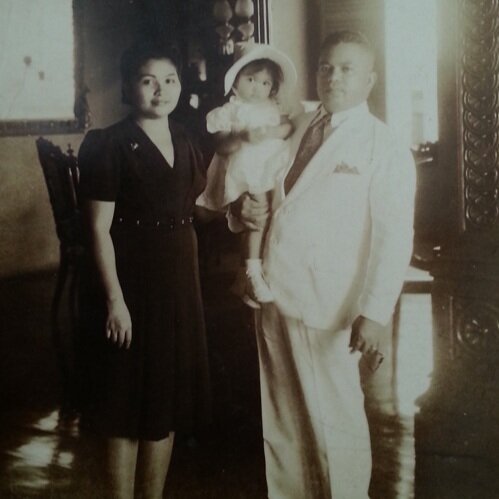

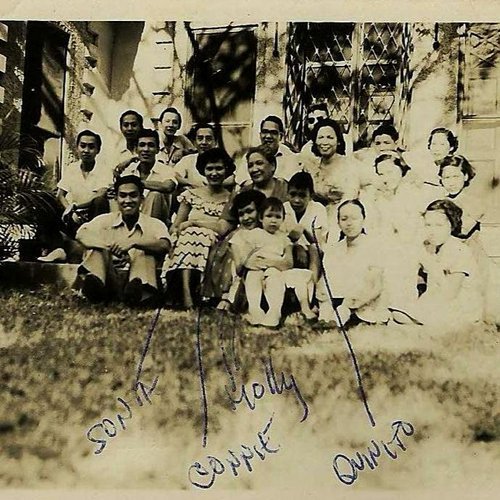

I never got to know my father's father, Angkong Yu Kiong, or “Angkong” to me and my cousins. He died ten years before I was born—and no, he did not teach Papa to cook, my father said, even though Angkong was excellent in the kitchen.

Angkong preferred to cook with kitchen doors tightly shut. No one, not one of his ten children, was allowed to venture in to learn the secrets of his cooking—like how he used “Ngo Hyong,” a Chinese five spice combination, to flavor his juicy “hong ba," his version of adobo, my Auntie Claire's favorite.